Does gamification satisfy needs? A study on the relationship between gamification features and intrinsic need satisfaction

Intrinsic motivation is commonly considered as the most productive force behind people’s behavior [10][34]. However, it is often observed that people lack intrinsic motivation towards different activities they would like to undertake. Thus, many companies, educational institutions and workplaces are competing for these people’s motivational resources. In an educational context, intrinsic motivation and the autotelicy of learning are considered as one of the highest pinnacles of successful education[9][28][32]. In the marketing context, the main goal of customer relationship building is to develop a customer who loves the product and is a fan of the brand [1][20]. Similarly, in the workplace, an employee who enjoys work and is more productive as a result is considered to be a success by any HR department[2][21].

In games, however, it is generally observed that we are often rivetingly engaged and intrinsically motivated, as well as being able to derive cognitive, emotional and social benefit [6][13][15][23][25][28][33][43]. As inspired by these positive observations of games, gamification[7][16][19] has emerged as a technology trend that attempts to further transfer these benefits to a variety of services and systems, and to further increase their autotelic affordance of “non-gaming” contexts (See [24]), such as health [3][17][22], education[5][12][39], work [8][35], crowdsourcing [26][29], marketing management [19][27][44] as well as science[30][40].

Not surprisingly as a consequence, in 2017, popularly the global gamification market was valued at USD 2.17 billion and is estimated to reach USD 19.39 billion by 2023 [31]. However, the practical failures have made many firms lose confidence in gamification. Especially in the business domain, 80% of current gamified applications were estimated to fail to meet their objectives due to poor design [14]. Because of these doubts, practitioners have started to question the effectiveness of gamification. Therefore, in the practitioner realm, a looming question is still relevant as to how companies and organization should implement gamification for it to have the positive effect it is hyped to have – be it on users, consumers, students or employees.

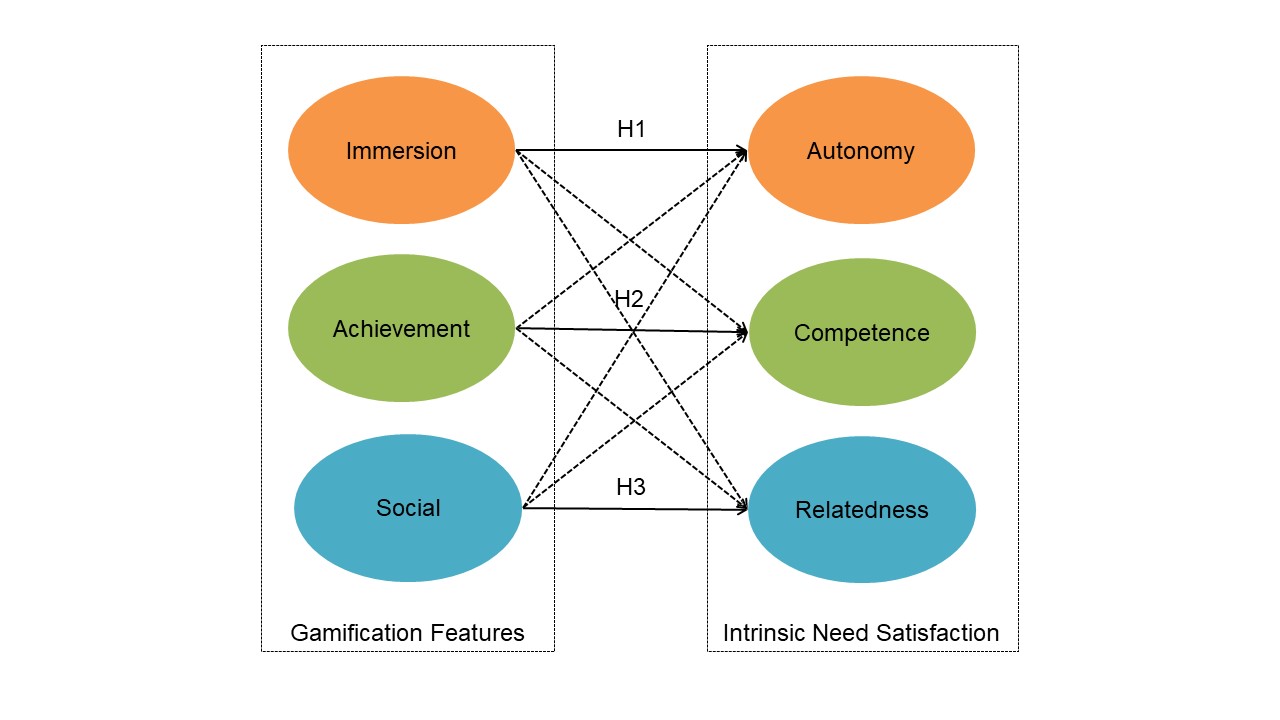

The majority of studies and reviews of empirical studies on gamification indicate that in the majority of cases, gamification has had a positive effect on motivations and behaviors [16][24][37][41]. However, more granular research on how different gamification features affect certain motivations has been slow to emerge[16][24][38]. Currently, there still has been a “black box” surrounding the understanding of the mechanisms of how gamification affects our motivations and behaviors [16][24]. One of the main theoretical lenses adopted in gamification research is that of self-determination theory[36][19][24][38] which posits that satisfaction of three primary intrinsic needs (autonomy, competence and relatedness) can lead to autotelic behaviors[10][34][11][18][4][42]. However, only a few studies exist that investigate the relationship between different categories of gamification and intrinsic need satisfaction.

Thus, in this study we aimed to fill this theoretical and practical gap by investigating the relationships between the user (N = 824) interaction with gamification features (immersion, achievement and social-related features) and intrinsic need satisfaction (autonomy, competence and relatedness) in Xiaomi and Huawei online gamified communities that represent two large technology product-related online brand communities in China through a survey-based study. The study’s main contributions were twofold: firstly, the study provided sought-after results about the relationship between gamification and intrinsic motivations, contributing to both the body of gamification literature as well as to the developer repertoire of understanding of how different game designs can affect their users. Secondly, the study provided an example of how to reach a balance between the more economic approach of treating gamification systems as single stimuli or investigating each gamification feature independently through a full experimental design which would normally be an unrealistic undertaking.

This paper is structured as follows. The next section covered the literature review including the theoretical background of gamification and intrinsic need satisfaction which support the three hypotheses in this study. Section 3 included the empirical study, explaining the research methodology and analyzing structural equation models. Section 4 provided a detailed discussion of the results, theoretical contributions and practical implications. The last section made the conclusion for this study and points out the future research areas based on the limitations.

Does gamification satisfy needs? A study on the relationship between gamification features and intrinsic need satisfaction

Nannan Xi

Juho Hamari

Citation: Xi, N., & Hamari, J. (2019). Does gamification satisfy needs? A study on the relationship between gamification features and intrinsic need satisfaction. International Journal of Information Management, 46, 210-221.

Please see the paper for full details:

Researchgate

Journal

Abstract

Gamification is increasingly used as an essential part of today’s services, software and systems to engage and motivate users, as well as to spark further behaviors. A core assumption is that gamification should be able to increase the ability of a system or a service to satisfy intrinsic needs, and thereby the autotelicy of use as well as consequent change in beneficial behaviors. However, beyond these optimistic expectations, there is a dearth of empirical evidence on how different gamification features satisfy different dimensions intrinsic needs. Therefore, in this study we investigate the relationships between the user (N = 824) interactions with gamification features (immersion, achievement and social -related features) and intrinsic need satisfaction (autonomy, competence and relatedness needs) in Xiaomi and Huawei online gamified communities that represent two large technology product-related online brand communities in China through a survey-based study. The results indicate that immersion-related gamification features were only positively associated with autonomy need satisfaction. Achievement-related features were not only positively associated with all kinds of need satisfaction, but also the strongest predictor of both autonomy and competence need satisfaction. Social-related gamification features, were positively associated with autonomy, competence and relatedness need satisfaction. The results imply that gamification can have a substantially positive effect on intrinsic need satisfaction for services users.

References

[1]Aroean, L. (2012). Friend or foe: In enjoying playfulness, do innovative consumers tend to switch brand? Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 11(1), 67–80.

[2]Amabile, T. M., Hill, K. G., Hennessey, B. A., & Tighe, E. M. (1994). The work preference inventory: Assessing intrinsic and extrinsic motivational orientations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66(5), 950–967.

[3]Alahäivälä, T., & Oinas-Kukkonen, H. (2016). Understanding persuasion contexts in health gamification: A systematic analysis of gamified health behavior change support systems literature. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 96, 62–70.

[4]Baard, P. P., Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2004). Intrinsic need satisfaction: A motivational basis of performance and weil‐being in two work settings. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 34(10), 2045–2068.

[5]Christy, K. R., & Fox, J. (2014). Leaderboards in a virtual classroom: A test of stereotype threat and social comparison explanations for women’s math performance. Computers & Education, 78, 66–77.

[6]Chou, T. J., & Ting, C. C. (2003). The role of flow experience in cyber-game addiction. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 6(6), 663–675.

[7]Deterding, S., Dixon, D., Khaled, R., & Nacke, L. (2011). From game design elements to gamefulness: Defining gamification. In Proceedings of the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference.

[8]Dale, S. (2014). Gamification: Making work fun, or making fun of work? Business Information Review, 31(2), 82–90.

[9]Deci, E. L., Vallerand, R. J., Pelletier, L. G., & Ryan, R. M. (1991). Motivation and education: The self-determination perspective. Educational Psychologist, 26(3-4), 325–346.

[10]Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268.

[11]Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2008). Self-determination theory: A macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Canadian Psychology, 49(3), 182–185.

[12]Filsecker, M., & Hickey, D. T. (2014). A multilevel analysis of the effects of external rewards on elementary students’ motivation, engagement and learning in an educational game. Computers & Education, 75, 136–148.

[13]Granic, I., Lobel, A., & Engels, R. C. (2014). The benefits of playing video games. The American Psychologist, 69(1), 66–78.

[14]Gartner (2012). Gartner says by 2014, 80 percent of current gamified applications will fail to meet business objectives primarily due to poor design. Stamford, CT, November 27, 2012. Available athttp://www.gartner.com/it/page.jsp?id=2251015.

[15]Hamari, J., & Keronen, L. (2017). Why do people play games? A meta-analysis. International Journal of Information Management, 37(3), 125–141.

[16]Hamari, J., Koivisto, J., & Sarsa, H. (2014). Does gamification work?—A literature review of empirical studies on gamification. In Proceedings of the 47th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS), 3025–3034.

[17]Hamari, J., & Koivisto, J. (2015). “Working out for likes”: An empirical study on social influence in exercise gamification. Computers in Human Behavior, 50, 333–347.

[18]Hagger, M. S., Chatzisarantis, N. L., & Harris, J. (2006). From psychological need satisfaction to intentional behavior: Testing a motivational sequence in two behavioral contexts. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 32(2), 131–148.

[19]Huotari, K., & Hamari, J. (2017). A definition for gamification: Anchoring gamification in the service marketing literature. Electronic Markets, 27(1), 21–31.

[20]Hollebeek, L. D. (2011). Demystifying customer brand engagement: Exploring the loyalty nexus. Journal of Marketing Management, 27(7-8), 785–807.

[21]Isen, A. M., & Reeve, J. (2005). The influence of positive affect on intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: Facilitating enjoyment of play, responsible work behavior, and self-control. Motivation and Emotion, 29(4), 295–323.

[22]Jones, B. A., Madden, G. J., & Wengreen, H. J. (2014). The FIT Game: preliminary evaluation of a gamification approach to increasing fruit and vegetable consumption in school. Preventive Medicine, 68, 76–79.

[23]Koster, R. (2005). A theory of fun for game design. Scottsdale, AZ: Paraglyph Press.

[24]Koivisto, J., & Hamari, J. (2019). The rise of motivational information systems: A review of gamification literature. International Journal of Information Management, 45, 191–210.

[25]Lo, S. K., Wang, C. C., & Fang, W. (2005). Physical interpersonal relationships and social anxiety among online game players. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 8(1), 15–20.

[26]Lee, J. J., Ceyhan, P., Jordan-Cooley, W., & Sung, W. (2013). GREENIFY: A real-world action game for climate change education. Simulation & Gaming, 44(2-3), 349–365.

[27]Lucassen, G., & Jansen, S. (2014). Gamification in consumer marketing-future or fallacy? Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 148, 194–202.

[28]Malone, T. W. (1981). Toward a theory Science, 5(4), 333–369.

[29]Morschheuser, B., Hamari, J., Koivisto, J., & Maedche, A. (2017). Gamified crowdsourcing: Conceptualization, literature review, and future agenda. International Journal of Human-computer Studies, 106, 26–43.

[30]Morris, B., Croker, S., Zimmerman, C., Gill, D., & Romig, C. (2013). Gaming science: The “Gamification” of scientific thinking. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 607.

[31]Mordor Intelligence (2018). Gamification market size – segmented by deployment mode (On-premises, cloud), size (Small and medium business, large enterprises), type of solution (Open platform, closed/ enterprise platform), end-user vertical (Retail, banking, government, healthcare), and region – growth, trends, and forecast (2018-2023)Available.

[32]Niemiec, C. P., & Ryan, R. M. (2009). Autonomy, competence, and relatedness in the classroom: Applying self-determination theory to educational practice. School Field, 7(2), 133–144.

[33]Przybylski, A. K., Rigby, C. S., & Ryan, R. M. (2010). A motivational model of video game engagement. Review of General Psychology, 14(2), 154–166.

[34]Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. The American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78.

[35]Robson, K., Plangger, K., Kietzmann, J. H., McCarthy, I., & Pitt, L. (2016). Game on: Engaging customers and employees through gamification. Business Horizons, 59(1), 29–36.

[36]Rigby, S. (2015). Gamification and motivation. In S. P. Walz, & S. Deterding (Eds.). The gameful world: Approaches, issues, applications (pp. 113–137). MIT Press.

[37]Sailer, M., Hense, J., Mandl, H., & Klevers, M. (2013). Psychological perspectives on motivation through gamification. Interaction Design and Architecture(s) Journal, 19, 28–37.

[38]Seaborn, K., & Fels, D. I. (2015). Gamification in theory and action: A survey. International Journal of Human-computer Studies, 74, 14–31.

[39]Simões, J., Díaz Redondo, R., & Fernández Vilas, A. (2013). A social gamification framework for a K-6 learning platform. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(2), 345–353.

[40]Sørensen, J. J. W., Pedersen, M. K., Munch, M., Haikka, P., Jensen, J. H., Planke, T., et al. (2016). Exploring the quantum speed limit with computer games. Nature, 532, 210–213.

[41]Su, C. H., & Cheng, C. H. (2015). A mobile gamification learning system for improving the learning motivation and achievements. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 31(3), 268–286.

[42]Van den Broeck, A., Vansteenkiste, M., De Witte, H., Soenens, B., & Lens, W. (2010). Capturing autonomy, competence, and relatedness at work: Construction and initial validation of the Work‐related Basic Need Satisfaction scale. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(4), 981–1002.

[43]Vesa, M., Hamari, J., Harviainen, J. T., & Warmelink, H. (2017). Computer games and organization studies. Organization Studies, 38(2), 273–284.

[44]Xi, N., & Hamari, J. (2019). The relationship between gamification, brand engagement and brand equity. In Proceedings of the 52nd Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS).

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.